A life / Melnikov House

Arbat, residential district of Moscow, 1927. The Russia of change. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, and with Bolshevik ruling the Soviets under Lenin’s command, the USSR is born. This new Soviet Union would get entangled in the web of totalitarianism when, in 1927, an all power-possessing ruler arises: the ascension of Stalin dramatically defined the transformation of Soviet society, sculpting a new face of the country, characterised by collectivisation and industrialisation.

In such a political and social context, architecture, the main channel of propaganda and subliminal messages throughout history, wasn’t left aside. The revolutionary vanguards, waving the banner of constructivism, were imbued with an aesthetic search for provocative, free forms and functionality and found themselves blinded by a new wave of architecture.

In the middle of this landscape, the Melnikov house was built, home for the last 45 years to the architect Konstantin Stepanovich Melnikov. This work would be a turning point in the life of the artist: his own home became his most renowned and appraised masterpiece, but also his most bitter.

With the passing of the times of the great Bolshevik revolution and the emergence of the new architectural language which ensued, Melnikov started to conceive his house as an experimental prototype, created from an intimate, thoughtful, purist and almost abstract perspective, yet still adequate as a working class’ home. However, with Stalin driving his home country towards a society soaked only in tradition, and systematically forbidding any hint of modernism, the Melnikov house was considered a perversion against the new regime’s attempts at producing monumental, neoclassical architecture.

Thus began the downfall of the architect, who would end up forced to spend the rest of his days under house arrest in the home he built for and by himself, away from teaching and his profession as an architect , and forced to dedicate himself to painting.

Today we take a nostalgic look at the house, tinted with a common admiration for the classics, in admiration of its modernist spirit, Corbusian geometry and freedom, social and symbolic sense and, most importantly, its dreamy, innocent nature. From Melnikov’s perspective, the most important feature of his work, particularly in his house, was neither functionalism nor adaption to the environment, but the architecture itself. Thus the architect created his home exactly as he had dreamt it.

Melnikov’s house caused great interest among his contemporaries because of the housing problem that the USSR faced at the time: it stood as a prototype, an inexpensive and easy-to-build model which could be replicated. Years later it would be its formal features that would spark interest.

Even the construction materials, as limited as they were, were wisely applied to optimise the house’s uses. Melnikov therefore made very efficient use of the scarce resources available to design a structure that would allow him to develop both his creativity and expressiveness: made of brick and wood (rhythmically drilled, thick, load bearing walls and light, reticular reinforcements made from laminated wood), and cement made from compressed debris instead of concrete.

“Scarcity forces us to find new solutions […] building for ourselves, by our own means and especially with such risk for our families’ well-being, is therefore a genuine impulse, invading our emotions, driving us to easily make extraordinary and unpredictable findings and replacing the path upon which our lives would have otherwise unfolded as routinely as that of a mole.”

Konstantin’s house was thus built following an eccentric version of free floor and façade, constituted by two hollow cylinders, thanks to the structural walls which represent the whole enclosure. The main section also had a free design, like a spatial explosion in which simple and double-height areas were dilated and compressed at an irregular pace in comparison to the exterior of the building. The curved façade was also designed following the principles of economical geometry: 59 hexagonal gaps setting up a talking composition over the house’s irregular symmetry, whose 5 horizontal lines prevent one from recognising the house’s various floors, thus altering the perception of its size.

In this architectural work we see the strange meeting and blurring of the most ancient and symbolic architecture through intersecting circles, the vanguards of architecture through its constant search for abstract geometry and the economical and functional needs of socialist society. From this mixture, a timeless construction was born.

Now, with the impending 40th anniversary of Melnikovs’s passing, his inarguable masterpiece hits the news again, but this time due to its conservation problems. The old walls and foundations, now over 83 years old, have noticeably deteriorated over the years, especially during the last months.

The perilous situation of the house has been made known by Natalia Melikova, a recently graduate from the Academy of Art in San Francisco, in her research project, who wrote from Moscow, warning about the dangers threatening the Russian vanguard’s house.

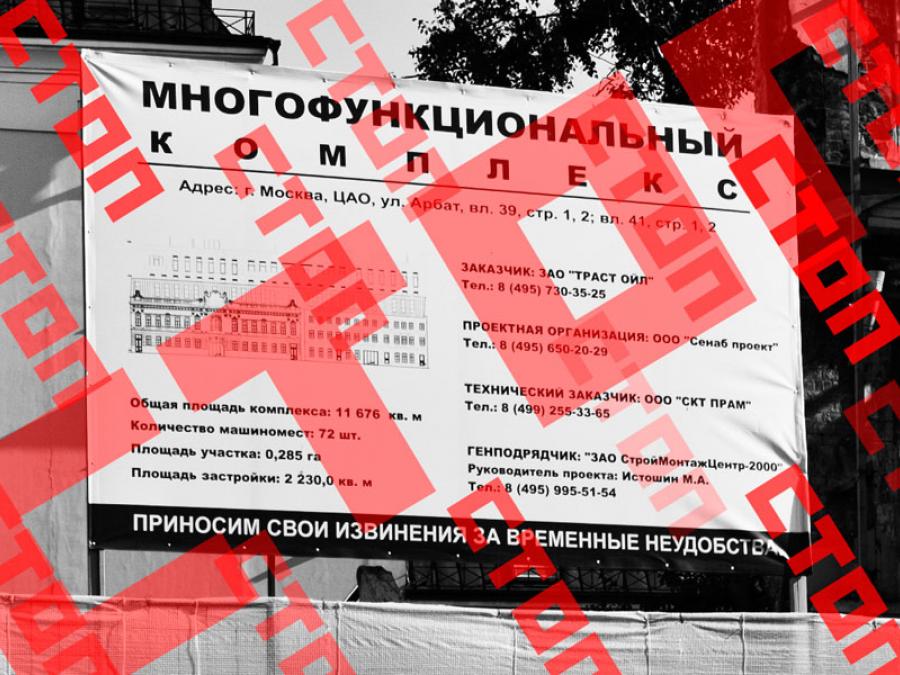

As Natalia explains in her article, some groups are eager to see the decay of the house, so it can be definitively demolished. The structural deterioration has worsened since August 2012, following the aggressive demolition of buildings adjacent to the house. The clear, yet unacknowledged negative effects of the neighbouring demolitions have pushed the house to the brink of collapse. However, the debate keeps revolving around the ownership of the house.

“All of this is happening with the simple intention of destroying the house. They can’t just tear it down because of the huge negative reaction it would trigger. So, both houses either side of Melnikov’s house have been destroyed, causing underground movements and instability. Now they are planning to build a dam so that the house falls on its own. And once it happens, they’ll say, “What did you expect? The house was old… and now it’s dead, finished,” explains Ekaterina Viktoronova, Melnikov’s granddaughter, who still lives in the house and is trying to protect it so that she can fulfil her grandfather’s wishes.

Within architectural circles, the cry can be heard for the restoration of the house, based upon its indisputable worth as a piece of art and valuable example of turn-of-the-century Soviet architecture. Numerous figures such as Kenneth Frampton, Peter Eisenman, Steven Holl, Rem Koolhaas, Fumihiko Maki, Bernard Tschumi, Alvaro Siza, Ginés Garrido or Juhani Pallasmaa have already signed a petition demanding of the authorities the restoration and upkeep of the building as a public museum, together with compensation to the Melnikov family for their efforts in the conservation of the building during the 40 years since the death of the architect.

Furthermore, they have asked for the “suitable gathering and preservation of every Melnikov-related Russian archive, preferably allocated within a public museum set up alongside the house, where they can be studied and consulted by architects and researchers.”

We hope that their voices will be heard and that this historical work will be known by future generations, not only through black and white photographs.

Text : Ana Asensio Rodríguez / Photographies: Do.Co.Mo.Mo / Written for Plataforma Arquitectura / Cita:Asensio, Ana. “Una vida / La casa Melnikov” 27 Apr 2013.